The 6th Street Disaster - 21 May 1885

John J. Sullivan was busy working

on accounts in his second floor office.

A sudden rash of business had come in just over a month ago and he and

his employees were struggling to push paper through the printing presses to

meet deadlines. Sullivan was the senior

member of his firm, the Sullivan Printing Company, which had been established

early in 1883 in the five story building at No.19 West 6th

Street. With the increase in business he

had been forced to expand his operation rapidly. Where only a few months earlier the entire

concern was run from the second floor, the bindery portion of the business was

now managed on the fifth floor. Two

weeks ago, to help process the work, Mr. Sullivan added seven new girls to the

staff of young women working in the upper level of the building.

Lizzie Meyers had just returned

from lunch and was employed in the fifth floor bindery with twelve other girls

in the front workshop. Will Bishop and

three additional girls were engaged in a small back room on the upper

level. Lizzie had been hired by Sullivan

two years earlier at the age of fifteen.

She was in a good mood and her mind was focused on the Press Feeders

Picnic a little over a week from today. Prior

to leaving her house this morning she had mentioned her excitement to her

mother and spoke of how she looked forward to wearing the new dress she just

purchased for the occasion.

Henry

Woodson was just starting his day. He

had been between jobs for some time and was living in a back room behind John

Regan’s Saloon, across the street from the Sullivan Company. Woodson was black, with an athletic build for

which Regan saw potential. Soon he was

backing Woodson in boxing matches where Henry earned the nickname, “The Black

Diamond.” Henry had been slow to get out

today but a commotion on the street grabbed his attention and he was headed to

the front window to see what was happening on the street.

The

boys at the three’s firehouse on 6th Street, just a couple of blocks

from Sullivan’s printing establishment, had been on the job all morning. The horses had been fed and tended to and the

station was put in order for the day.

Their steam fire engine, The Citizens’ Gift, was gleaming, having also been

cleaned that morning. The firemen from

Hook and Ladder Company One shared quarters with the engine company and they

too had touched up the ladder wagon that morning. Fire Chief Lew Wisbey and Assistant Fire

Marshal J. S. Donovan were among those with offices upstairs in the large

building which also served as the fire department headquarters.

The Gifts' Firehouse - Engine Co.3 & Ladder Co.1

Photo Compliments of the Stelter Collection

John Sullivan was seated at his desk when he was startled by the cry of one of his employees, eighteen year old Johnny Meyers. He hurried out to see what the uproar was all about and he found Johnny running away from the printing presses with his cloths on fire. Thomas Hardin, a supervisor in the second floor printing room, had sent Johnny to the first floor to fill a can of benzene to be used for cleaning the press rollers. When Johnny returned he stumbled in the dark passage behind a press near the open elevator shaft. As he fell forward the tin can struck the nearby printing press and the glass jar that contained the benzene inside the tin housing broke. He tried to stop the benzene from spilling with his hands but it was no use. In a matter of seconds the vapors from the highly flammable liquid reached the burning gas jet on the ceiling over the printing press igniting a small fire. Johnny ran over to Mr. Hardin who quickly managed to put his clothes out. Mr. Sullivan saw the small blaze and quickly passed through it to obtain a fire blanket with the intention of smothering it. He returned to find the fire had grown to a size he could no longer manage. The flames had been pulled into the flue-like elevator shaft and were rapidly moving up through the building. Recognizing the imminent danger posed to the employees on the upper levels Mr. Sullivan yelled out “someone save the girls!” About the same time his twenty-one year old cousin, also named John Sullivan, cried out “Fire,” as he rushed for the stairway. Heavy smoke began to fill the building as the woodwork in and around the elevator started to burn out of control. Everyone in the lower level of the building was yelling “fire” and streaming out of the building.

As people were reaching the exits, pedestrians on the street were beginning to notice the heavy black smoke rolling up from behind the building. A crowd started to gather and someone sprinted to fire box 36 at the corner of 6th and Main Streets and pulled it, sending an alarm to the fire department. Young John Sullivan was joined by another of his cousins, Will Sullivan, who was about his age. The two men dashed up the stairs yelling “fire” and hoping to reach the girls in time. Starting at the third floor the lone stairway to the upper two floors wrapped around the elevator shaft and it was already filling with choking smoke. John and Will reached the fifth floor where the girls were working at their stations, unaware of the peril they now faced. The startled girls looked up to see the boys enter the area just as they noticed smoke and fire spilling forth from the elevator shaft. Panic took hold of the girls. Will Bishop and those girls working in the back room rushed forward. By now the stairway was filled with smoke and could no longer serve as an exit. Everyone started to run toward the front windows. Will had been thinking of using the roof hatchway as an exit all along. He and John would sometimes use the short ladder that hung in the back of the building to get up to the roof, joining the girls for lunch or to watch a passing procession. The ladder was nowhere to be found and Will started to panic. His face, arms, and ears were starting to burn. He swiftly stacked books on the table under the hatch and jumping, grabbed the ledge and pulled himself to safety on the roof above.

On the sidewalk below a massive crowd was growing. They were screaming and calling to the girls who started to appear at the windows. It was this noise that caught the attention of Henry Woodson and sent him to the window to see what was going on. When he reached the glass he was met with a shocking scene of horror. He watched as Lizzie Meyer jumped from the fifth floor window. The crowd had seen her reach the window. They watched as she moved out onto the sill. Smoke was billowing out around her. People on the street called to her to wait but she had resolved not to burn. Only moments earlier she had been thinking of wearing her new dress and now she was dying on the sidewalk. Bystanders carried her to a neighboring business but she could not be saved. Almost immediately after Lizzie made her fateful plunge another terrified face appeared in the window above the crowd. It was Mrs. Anne Bell. She too was determined to find refuge from the heat and despite the pleas from the people below, she also jumped. A patrol wagon conveyed her to the hospital but she was dead only a short time later.

Image from The Daily Graphic, New York City - May 25, 1885

B.Houston Collection

By now people were taking action in an effort to prevent further tragedy. Harry Kinsley and Joseph Schroeder, both employees of the business immediately to the west of the Sullivan concern at No.21 West 6th Street, climbed out the window of their building onto Sullivan’s roof. They had sixty feet of inch thick rope they used to hoist supplies to the upper floors. They planned to drop it to the girls at the windows and lower them to safety. Inside the situation was desperate. Young John Sullivan, who had heroically rushed up the stairs in an effort to save the girls, was doing what he could to keep fifteen year old Emma Pinchback and twenty-four year old Josie Hocks from jumping. The girls had tried to pile furniture up to reach the roof hatch but they could not make it to the opening. The room was getting hot and there was little time to spare. The girls were in a panic and ran forward, knocking out the front windows when they reached them. Josie couldn’t take the heat and smoke any longer. She moved onto the window sill. There she could see blood on the sidewalk below. The crowd shouted at her to wait for the firemen. Looking down 6th Street she could see the fire engine and ladder wagon rushing to the scene. She was determined to wait but thought they might not reach her in time. It was then that the rope from above dropped within her reach. Without hesitation she grabbed hold. The two men on the roof strained to lower her safely.

Henry Woodson bounded down the stairs after watching Lizzie Jump. He opened the door on the street just as Anne Bell crashed in a heap to the ground. By now he was sprinting into the mass of people. Looking up he could see Josie grab hold of a rope. She was being lowered and struggling to hold on. As she passed outside the windows on the third floor a blast of smoke and heat struck her in the face and her grip failed. Henry, still pushing forward, reached her just in time to catch her in his arms, breaking her fall and saving her life. Her ankle was fractured and his arms and shoulders badly strained but he had saved her from the unforgiving ground that had already claimed the lives of two of her coworkers. Kinsley and Schroeder, on the roof, quickly pulled the rope back up. It was then that Emma spotted the lifeline and made her move. She latched on and the men on the roof lowered her as she slid down the rope. Her hands were burned and her arms scorched from the fire but she would also survive. John Sullivan had to get out. He could wait no longer. Smoke kept him from seeing into the room but there were no other girls at the windows. The rope was drawn back up and he jumped on. The crowd cheered loudly as he escaped the smoky furnace. It appeared as though the young man, who thought first of the girls before considering his own safety, would be saved. Suddenly, as he reached the top of the third floor windows the rope snapped. It had been weakened by exposure to the fire and heat from the first two rescues. Young John Sullivan plunged to the ground below. The mass of people drew back in horror as the sickening thud filled their ears. His older brother Dennis Sullivan, one of the proprietors of the business, picked the broken and unconscious man up and carried him to Regan’s Saloon where he laid him on a billiard table. Soon after he was loaded onto a patrol wagon and rushed to the city hospital. John had sustained severe burns, and fractured his jaw, pelvis, and legs among other injuries. He died an hour after arriving at the hospital.

Young John Sullivan - One of the Hero's of the 6th Street Disaster

Cincinnati Enquirer - May 22, 1885

Kinsley

and Schroeder had felt the rope become slack and knew it had snapped. They were back away from the ledge, straining

to lower the rope and unable to look over the edge while doing so. When the rope broke they ran forward but their

view was clouded by the heavy smoke rolling up from the windows below. They started to deploy a second rope but the

crowd yelled for them to get back. The

smoke was thick and they were in a dangerous position. People below indicated no one was waiting at

the windows so they withdrew to the safety of the building from which they had

come. Some men in the crowd brought a

tarpaulin forward. Somehow Nannie

Shepherd had managed to find her way to the third floor. She was also on the window sill and the men

below pulled the tarpaulin tight and called for her to jump. She hit the mark but the tarp was pulled from

the hands of the men holding it and she struck the sidewalk. She suffered a deep gash to the back of her

head and had some painful burns on her lower legs but her fall had been broken

enough to save her life. In the panic

and confusion Will Bishop had made his way onto another of the fifth floor

window sills. He had suffered severe

burns to the head, body, face, and hands but he was determined to be

rescued. Time slowed for those people

trapped in the building and for the crowd that was witnessing the tragedy

unfold. It had only been a few minutes

since Box 36 sent an alarm to the fire department. The firemen now arrived. As the horses pulled the apparatus up to the

building the firemen jumped to action.

Chief Wisbey immediately ordered the big five story ladder be raised. Assistant Fire Marshal Donovan called in a

general alarm, bringing most of the department to the scene. A web of telegraph wires ran over the street

outside the building, making the raising of ladders more difficult. Finally with the ladder in place, they were

able to save Bishop. More and more

ladders were raised to the various floors and water played into the windows. The heaviest of the fire was on the fifth

floor. Soon the bulk of the blaze was

knocked down.

Assistant Fire Marshal John C. Donovan who sounded the general alarm at the Sullivan Blaze

Photo Compliments of the B.Houston Collection

Firefighter

M. J. Higgins and pipeman Peter Kuhn were among the first men to climb through

the windows into the fifth floor looking for victims. The room was still filled with heavy smoke

and hot spots had yet to be extinguished.

Moving into the workshop they could see six bodies huddled together

under an open roof hatch with furniture and papers piled up under it. A space of about seven feet separated the

pile from the opening. Chief Wisbey

quickly made his way up a ladder to the fifth floor and stepped into the

smoke-filled bindery. He stepped on

something soft as he climbed over the window sill. It was another of the unfortunate girls who

did not make it out in time. Several

bodies could be seen on the floor near the windows in addition to those under

the hatch. The firemen started to choke,

coughing on the thick smoke before being forced back out to the windows where

they leaned out for fresh air. Two

firemen had breathed in so much they vomited.

Another effort was made to search the room but no living person was

found. The smoke was so thick it was

clear no one who had been in the room was alive. The firemen were forced back outside seeking

refuge on the ladders by which they had gained entry. They would have to wait for some of the smoke

to clear before going back in.

Most of

the floors sustained more damage from the water than the fire. The building had been saved as firefighters

made quick work of the blaze. Some

firemen had made entry in the lower levels of the building and with the smoke

starting to clear they were progressing up the stairs. In the second floor they found extensive

charring around the elevator. As they

moved further up the fire damage was found to be greater. The stairs around the elevator shaft from the

third floor up were described as charred and weakened. Care was used moving up. No victims were found on the fourth floor and

some of the men thought things may not be so bad. When they entered the fifth floor their view

was obscured by the haze of smoke but steaming piles of what appeared to be

rags were seen scattered about the floor.

These were the bodies of the girls who had not managed to escape.

Police had

their hands full keeping the crowd under control below. People were trying to get a view of the

firefighters and police as they carried the bodies down the stairs to waiting

patrol wagons to be carried to Habig’s Morgue.

Five bodies filled the back of the first wagon which was covered with a

tarp before pulling away. Another patrol

wagon and an express wagon, which had been pressed into service, pulled

forward. Rumors of the number of bodies

brought down spread from the front of the crowd back. Some in the group could take no more and

walked away, others were fixated on the grizzly scene, unable to look

away. Ultimately eleven bodies were carried

from the building.

The

patrol wagons left one crowd only to pull into another. This assembly had gathered outside Habig’s

Morgue. Here the bodies were carried

from the wagons up to the second floor where they were laid out in twelve zinc

lined ice boxes on the ground. Grieving

relatives would soon start to make their way up the stairs to view the bodies

one by one, until they identified their daughter, brother or wife. One of the first relatives to arrive was

Covington Policeman Robert Handle. His

twin twenty one year old sisters, Lizzie and Dorothea, worked for

Sullivan. He made the identification before

leaving with tears in his eyes. Both

girls were lost. Another horrible scene

was the arrival of the fifty year old widow Mrs. Lavan. An officer saw her coming and warned her of

the terrible scene but she insisted on going inside. She was looking for her three daughters,

Delia 23, Mary 17, and Kate 14. All

three were found inside. Mrs. Lavan had

lost all her daughters. One of her sons

helped her out of the room. Sisters

Katie and Mary Putan were also killed.

The girls each earning $4 per week were the principal income for their

family in Newport where their father had been out of work for a time. Eighteen year old Tillie Winn had only worked

for Sullivan for a day and a half and was found dead under the hatchway. Her widowed mother had died only a few weeks

prior. She would be laid to rest by her

siblings. Fannie Jones was twenty years

old. Her brother was able to identify

her thanks to a ring she wore on her finger.

Lizzie Meyers, the seventeen year old who was the first of the girls to

jump from the windows, was the only daughter of her widowed mother. A close friend of the family arrived to identify

sixteen year old Annie McIntyre. Her

sister had told their widowed mother of the fire but they were not sure Annie

was among those killed. The McIntyre’s

became aware of their loss when Annie’s body arrived at her home that evening

shortly after being identified. Her

brother noted to a reporter that just last week she had commented about how

difficult it would be to escape from Sullivan’s building in the event of a

fire. The last of the dead carried into

Habig’s was nineteen year old Katie Lowry who was identified by her brother. He nearly fainted upon viewing her. Katie’s sister had recently quit working for

Sullivan and now worked for another printing concern. At thirty-five years of age, Mrs. Anne Bell

was the oldest of the victims and the only married woman in the group. She had been the second woman to jump from

the building. After being transported to

the hospital she was later identified by her disabled husband who had been

injured in the war some years earlier.

She also left behind an eleven year old daughter. The twenty-one year old hero John Sullivan

had died shortly after arriving at the hospital. His brother Dennis had employed John for the

past two years. Dennis brought John’s

body back to the family home and their widowed mother and siblings.

The

proprietors of the Sullivan Company procured a carriage and spent the evening

traveling from one victim’s house to another.

They offered sympathy and what money they could give the surviving

members of each family. A reporter for

the Enquirer noted that they were broken with grief and blamed themselves for

not having provided better means of escape from the building. Indeed the building and its lack of safe

means of egress quickly became an area of public comment and criticism. The Bookbinders Union immediately passed a

resolution condemning the negligence of the owner and lessees of the

building. The Association of Stationary

Engineers took similar action.

Newspapers suggested that a simple expenditure of $50 for a fire escape

could have prevented any loss of life.

The enquirer described the action of those responsible as “rapacious

selfishness.” Throughout the next day

crowds continued to congregate at the site.

The cost of the fire also continued to grow. A fifteenth person, Nannie Shepherd, passed

away the morning after the fire at her home.

She had jumped into a tarp from the third floor and sustained a cut to

the back of her head. By this time the

story had been reported coast to coast.

The Chicago Tribune ran the headline, “Seventeen Human Lives Sacrificed

in a Cage-Like Building in Cincinnati.”

The New York Times proclaimed, “Fourteen Girls Perish, Burned to Death

in a Cincinnati Fire Trap.” Perhaps the

most revealing summation of the tragedy came from The Boston Post which

reported, “Cincinnati adds another to this year’s persistent long list of

horrors by fire. It is the same old

story of a tall building with no fire escapes and a single pair of narrow

smoke-stack stairs.”

The

General public sentiment echoed that of the newspaper headlines. It was widely felt that negligence was the

cause of the devastating loss of human life.

People pointed out similar buildings and situations and it was widely

believed that this same tragedy could easily repeat itself. Indeed, it was not the first time a fire of

this nature claimed a large number of lives in Cincinnati. Only two years earlier on September 03, 1883

a fire at the rag house of Henry Dreman and Company claimed nine lives in

similar circumstances. That building was

situated just down the street from the site of the present tragedy. It was not just the public demanding

action. The Board of Aldermen met and

passed a resolution calling on the city inspector of smoke and fire escapes to

carry out his duties of enforcement to the full extent of his ability. Mayor Amor Smith had been among the crowd as

bodies were removed from the building following the fire. He advised any employee who felt their establishment

was dangerous should write a letter to the inspector. He also indicated his plans to meet with John

Fehrenbatch, the new inspector of fire escapes and smoke, to make clear his

expectations.

Finger

pointing and confusion regarding who was responsible for the safety of the

building dominated the public statements made by the building’s owner W. B.

Smith and the lessees John J. Sullivan and his partners. Both indicated that in repeated discussions

with inspectors they were told that an escape was not required. The former inspector of fire escapes, who had

been responsible at the time for the inspection of the Sullivan Company, was

Nat Caldwell. Caldwell indicated that he

inspected the building on April 22, 1884.

Sullivan had just signed a lease for the entire building in March but

was only operating on the second floor.

The inspector told Sullivan that an escape was not required because no

person was working above the second floor.

Caldwell says he made clear that an escape would be necessary if that

situation were to change. In September

1884 Caldwell dispatched his assistant Richard Blake to conduct another

inspection. Blake was sent initially to

the neighboring Kinsley building because it had been ordered to put an escape in

place. Kinsley stated that there had

been a mutual plan to put up an escape to serve several of the buildings

together including the Sullivan concern.

Blake then called on Sullivan who indicated he was still not using any

of the upper floors and that he had never discussed any plans for a mutually

constructed fire escape. Blake did not

enter the building to check its occupancy, but because he was told the upper

floors were not being used he again advised Sullivan that an escape was not

required.

Coroner

Carrick started his inquest on Saturday May 23.

His investigation would attempt to ascertain both what the cause of the

fire was and who was ultimately responsible for the long list of dead and

injured. Dozens of employees, the

proprietors of the business, the building’s owner, witness, and firemen were

called to offer testimony. Most revealing

was the statement of proprietor John Sullivan who indicated that it was only in

the past 5 to 6 weeks that they had started using the upper floors due to a

sudden rash of business. He further

stated that they had not had time to bring the upper floors to proper

order. Former Inspector Caldwell’s

testimony was also enlightening. He told

of the resistance he had experienced in enforcing the fire escape law. Indeed it seemed many property owners viewed

the fire escapes as a means by which thieves could enter their buildings. Employees told mixed stories regarding what

instruction the received from the Sullivan Company regarding how to act in the event

of a fire. Some said they were told to

use the roof hatch and others claimed they had never been addressed with

respect to the subject.

Ultimately

it was an Ohio State Supreme Court ruling that would provide the basis for the

coroner to assign blame. Suits had been

filed against the owners of the property which housed the Dreman Company, where

nine lives had been lost under similar circumstances in 1883. Cincinnati Superior Court ruled that the word

“owner” as used in the statute requiring fire escapes, referred not to the

material owner of the premises but rather to the tenant engaged in the use of

the space. The coroner concluded inquest

number 114 at noon on May 26.

Considering the legal precedent that had been established by the suits

related to the Dreman fire along with all the testimony offered by the summoned

parties, Coroner Carrick determined that the proprietors of the Sullivan

Printing Company were solely responsible.

He stated that when they found it necessary to us the upper level of the

building it became their duty to provide for the safe escape of the employees

working there. The coroner softened his

judgment by calling attention to the fact that the proprietors immediately

thought first of their employees rather than themselves, and made efforts to

warn and save them. In conclusion

Coroner Carrick stated he hoped this event would serve to put the community on

notice and spur more rigid enforcement of the fire escape codes.

Sadly

incidents of this sort would continue to be repeated around the country for

years to come. Eventually a national

outcry would resonate after the deaths of nearly 150 people working in similar

circumstances at the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory in New York City on March 25,

1911. The Sullivan Printing Company Fire

was covered by newspapers around the country.

Cincinnati papers covered the event for nearly a week, reporting at

length on the fire, the victims, the investigation, and eventually the

litigation that followed the coroners ruling.

It remains the deadliest single fire event to have occurred in the City

of Cincinnati. Anyone who witnessed the

horrors of the Sixth Street Fire had the images of burned and mangled bodies

seared into their minds. Despite

widespread coverage by the press and the extended attention the event received

by the general public, it is essentially forgotten today. It is a sad truth that it took many similar

incidents to bring about meaningful change.

The fire and building codes that govern the construction and use of

structures today are the result of these difficult and tragic lessons

learned.

1887 Sanborn Insurance Map - W.6th Street between Walnut & Main

Sullivan's is indicated on the map at No.19 West 6th Street.

1887 Sanborn Insurance Map

Walnut is far left running top to bottom

Main runs through the image top to bottom and at the time was the divide between streets designated East/West Sullivan's is in the upper left corner (see detail map above).

This image is taken from the intersection of W.6th & Walnut Streets looking down W.6th Street in 1968

The 2 story structure labeled 78-1-25 occupies the site of the Sullivan Printing Company.

It is unknown what date the original 5 story structure was torn down.

The 2 story structure labeled 78-1-25 occupies the site of the Sullivan Printing Company.

It is unknown what date the original 5 story structure was torn down.

A modern view of the intersection pictured above.

The 10 story Times Star Building on Walnut Street is the only old building remaining in this view

Image: Google Maps

Image: Google Maps

The approximate location of the Sullivan Printing Company Fire as is appears today.

The site is now occupied by the 580 Building and the Trattoria Roma Ristorante.

Image: Google Maps

List of the victims of the 6th Street Disaster

Delia Lavan - 23

Mary Lavan - 17

Katie Lavan - 14

Lizzie Handle - 21

Dollie Handle - 21

Katie Puntan - 22

Mary Puntan - 19

Matilda Winn - 20

Fannie Jones - 20

Lizzie Meyers - 16

Annie McIntyre - 16

Katie Lowry - 19

Mrs Annie Bell - 35

John Sullivan - 21

Nannie Shepherd - 20

Twin Sisters killed in the fire

Cincinnati Enquirer - May 23, 1885

Fannie Jones - Killed in the fire

Cincinnati Enquirer - May 23, 1885

Cincinnati Enquirer - May 23, 1885

Nannie Shepherd - The last of those who died as a result of the fire

Cincinnati Enquirer - May 23, 1885

Miss Delia Lavan, the oldest of the three Lavan Sisters killed in the fire

Cincinnati Enquirer - May 22, 1885

Annie McIntyre - Killed in the fire

Cincinnati Enquirer - May 23, 1885

Cincinnati Death Index Card - John Sullivan listed as died from "accidental injuries at 6th St fire"

John J. Sullivan

Cincinnati Enquirer - April 09, 1897

John J. Sullivan, proprietor of the Sullivan Printing Company - After the fire Sullivan moved his business to a building at the intersection of Court & Broadway. Sullivan also was active politically. A friend of George Cox, Sullivan was appointed to serve on the Board of Supervisors - In September 1901 Sullivan was riding on the tailboard of a streetcar with his friend and former Mayor John Mosby. As the car passed over a narrow bridge his coat snagged on a large bolt pulling him from the running board. He was tossed over the railing and fell 25 feet to the rocky creek bottom where he broke his neck. A doctor traveling in his company reached him quickly but he was pronounced dead at the scene of the accident.

http://hdl.handle.net/2374.UC/386985

Post Update - Another image of the 6th Street fire found:

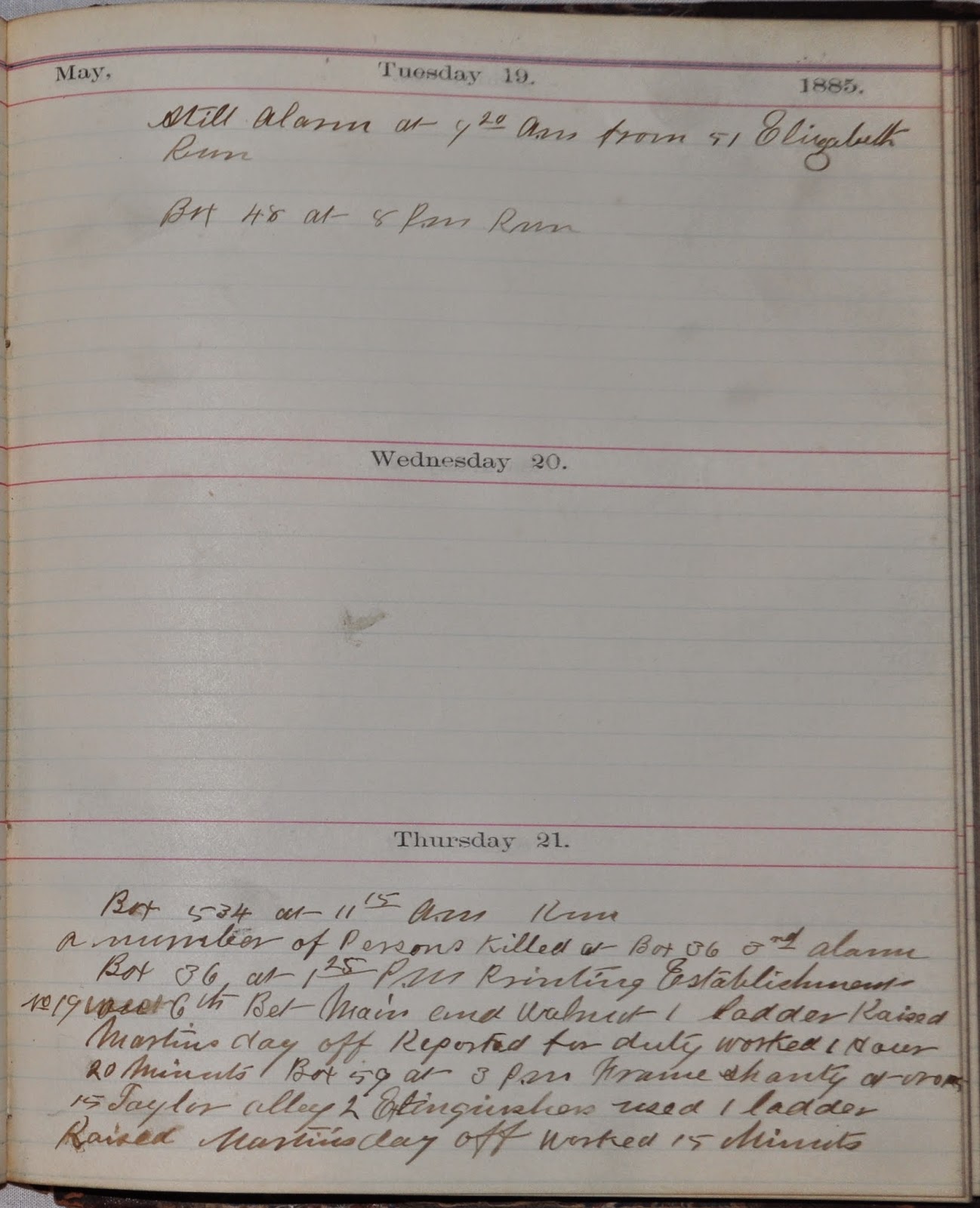

Post Update 27 Oct 2014: 1885 Company Diary Entries

Sources

Post Update - Another image of the 6th Street fire found:

Post Update 27 Oct 2014: 1885 Company Diary Entries

Engine Co.15 Company Diary

Sullivan Printing Co Fire - Entry on 21 May

Courtesy Cincinnati Fire Museum

Ladder Co.6 Company Diary

Sullivan Printing Co Fire - Entry 21 May

Notes: "A number of persons killed at Box36"

Courtesy Cincinnati Fire Museum

Sources

History of the Cincinnati Fire Department - 1895 - Publication of the Firemen's Protective Association

Pg.244-247

Cincinnati Enquirer - May 22, 1885 - A Hell Awful Tragedy of Fire

Chicago Tribune - May 22, 1885 - A Veritable Death Trap

New York Times - May 22, 1885 - Fourteen Girls Perish Burned to Death in Cincinnati

Louisville Courier Journal - May 22, 1885 - Sacrificed Awful Destruction of Life by a Fire at Cincinnati

Cincinnati Enquirer - May 23, 1885 - The Death Trap A Review of Thursdays Horror

Cincinnati Enquirer - May 24, 1885 - End of a Memorable Day of Funerals

Cincinnati Enquirer - May 25, 1885 - Fire Echoes Funeral of Katie Lowry

Cincinnati Enquirer - May 26, 1885 - Concluded Inquest Sullivan Fire

Cincinnati Enquirer - May 27, 1885 - The Coroners Verdict

Cincinnati Enquirer - September 27, 1885 - 6th Street Fire Damage Suits as a Result

Cincinnati Enquirer - September 26, 1901 - Toppled to Death John J Sullivan

Cincinnati Enquirer - September 28, 1901 - Splendid Display of Heroism By Colored Man

University of Cincinnati - Rare Books Archive & Library - Death Index Cards

Special Thanks

A special thanks to those people who have helped to gather sources for this inaugural blog post as well as those who offered advice in building the page:

B.Houston (CFD)

J.Stelter (CFD)

A.Senefeld - www.diggingcincinnati.com

Questions??? Comments... Feel free to start a discussion here! Thanks for reading.

ReplyDelete